|

Wound/Spasm

an explorative text by Patrick ffrench to accompany the work of Michael Clark

I am obsessed by the wound. We are fascinated by the wound. Forget the wound.

What is a wound? It forms from a puncturing, a tearing, a rupture, a piercing. Something pierces the surface of the skin, or another membrane, to leave a puncture, a tear, a slit. The wound is also a metaphor. It figures the rupture of something closed; the wound is something inflicted, with violence (the sense of rupture or transgression of a surface, of pushing through whatever divides or separates inside from outside). Thus, in a Christian (and post-Christian) era, the wound is both divine intervention in human territory, the mark of God, and a figure of the c**t, or, why not, the anus. The wound is the figure of a transgressive irruption of something other (whether divine, bestial, feminine, etc.) in a defined body, limited by the contours of the human, the phallic, the territorial ( terrestrial). The wound, in other words, is the necessary outside, affective force of a philosophy of the Subject, where this Subject is whole, masculine, ego-centred, you. Philosophies of the Subject produce their own transcendent outside, violence, other - whether as divine, feminine, unconscious, rhythmic, etc. We are obsessed with the wound because we live with a philosophy of the Subject – closed, whole, phallic, because we think of ourselves as inside, as a whole body limited by skin, which keeps us in. I am in here, in this body, incarnate. Spirit inhabiting flesh. I move around in this body, a whole, closed thing, a walking phallus. I am fascinated by the wound, by violent irruption, as whatever is outside, and which threatens this phallic enclosure.

Two stages in thinking beyond this paralysing deadlock, which keeps us in ethical stasis and sexual misery:

1) The wound is inside. 1) The wound is inside.Original difference at the heart of the Same, something in me more than me, inquiétante étrangeté: such terms have identified a wound that is internal, always already there, a constitutive lack or void in substance, around which it constitutes itself. For such philosophies the body is in a sense organised around an internal and original kernel of emptiness, a hole. Unrecognisable, unnameable amalgamation of visceral tissue. The wound fascinates us because it mimics, on the external membrane of the skin, the internal and original hole, which we attempt to fill, the lack which we want to make up for, and in making up for it are what we are. The body, here, is substance around the internal contours of a hole, of this defunct muscle. The equation is reversed, the limit is internal, the outside is in. There is something in me that isn’t me. But, despite the switch of outside in, this is still a question of rupture, of transgression, puncture and piercing. Is there a different way of thinking this, still?

2) The wound is a spasm. 2) The wound is a spasm.The Subject, ‘I’, is not an interiority. ‘I’ am not inside. ‘I’ consist of interrelations, shoots, tangles, spasmic thrusts and envelopes. The body is not an enclosure, limited by skin. The body is its form and its spasms, its movements. There is no surface to be pierced, no inside to be invaded, no interior in or out of which the alien is going to erupt. Think beyond this. The wound is a spasm, a fold. The body is a becoming, a transforming, a morphosing. The wound, the piercing an event in this transformative process, whereby whatever punctures experiments a different body, for a moment, with the thing it pierces.

Not to see these different ways of thinking as opposed, but rather to propose the last (the wound is a spasm) as the thought beyond the space we’re in, which we want to get out of. But there is a resistance: fascination, fetishisation, obsession, ritual. The fetishisation of the wound is where it functions as a limit, on the other side of which is immanent matter, indifference.

Pain is at this threshold. Think of pain in two different ways: as unbearable intrusion, or as experimented sensation. The plane of sensation takes you over the threshold on this side of which your body is a sad receptacle. It is a liberation, but it risks your dissolution.

The wound, the portrait as wound, wounding as ritual, performance, sacred rite fascinates because it is at a threshold, between the phallic body and the intimate life of immanence. You can’t just leap into a different way of thinking, of inhabiting your body.

© 2000 Patrick ffrench

Sacred Century

Religion in 20th century British Art

Level 2, Henry Cole Wing Victoria & Albert Museum

31 January - 9 June 2002

Open 10am - 5.40pm every day

Admission free

Sacred Century is a display of twentieth-century British art and design from the V&A's collection of prints, drawings and paintings, including some recent acquisitions from contemporary artists.

The display begins with the ebb and flow of tradition and innovation in the first half of the century. The medieval craft values of Phoebe Anna Traquair and Robert Anning Bell were a legacy of the Arts and Crafts movement of the late nineteenth-century. Tradition was challenged by the experiments of Wyndham Lewis, David Bomberg and Paul Nash, but the trauma of the First World War prompted a 'return to order' typified by the solemn delicacy of Gilbert Harding-Green's interpretation of the Pieta and Eric Gill's Crucifixion altarpiece for a war memorial chapel.

The tragedy of war has turned many artists towards religious subjects in the search for a visual language to match the scale of human suffering, Hans Feibusch's modern-day Pieta and Graham Sutherland's Thorn pictures being two examples inspired by the Second World War. Another response to the destruction was the churches' patronage of contemporary artists during Britain's post-war reconstruction, of which the new Coventry Cathedral was perhaps the crowning achievement.

The late twentieth century witnessed two contrasting trends in the relationship between art and religion: appropriation and diversity. Some artists deployed religious objects, symbols and icons in their secular investigations of representation, gender, self and the body. Meanwhile, alternative spiritual outlooks proliferated as other artists questioned or discarded the Judaeo-Christian tradition.

The display ends, however, with Michael Clark's sombre icon of wounded flesh....

Text extract to accompany Sacred Century Religion in 20th century British Art

© 2002 Victoria & Albert Museum

MICHAEL CLARK Wounds

7 March - 9 April 1994

Curated by Ian McKay

March sees the opening of WOUNDS - an exhibition of new work by MICHAEL CLARK. With the exception of his widely acclaimed double-sided portrait, "Vanitas", included in the NATIONAL PORTRAIT GALLERY exhibition "The Portrait Now", Clark's wound paintings have not previously been exhibited.

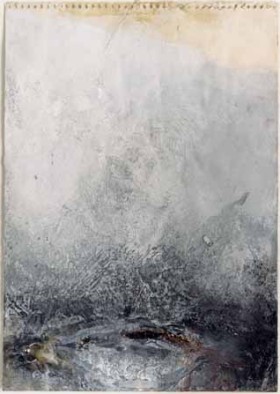

The exhibition has been curated by the writer and critic, lan McKay and includes Clark's renowned picture "Some May Lose Their Faith..." which is based on Holbein's painting of the dead Christ in the tomb. Adjacent to this will be shown the smaller, more intimate wound panels which were recently referred to in the Saturday Independent as "like Turner's interiors"; a reference to the poignant handling that Clark brings to his obsessive interest in human flesh, at once resembling the finest of Turner's landscape studies.

In the past, Clark's work has been shown alongside that of Rembrandt, Cezanne, Sickert, Bacon and Bomberg and, certainly in the context of the forthcoming exhibition, reference to Rembrandt's "Carcass of a Slaughtered Ox" is in-keeping with the sentiment that underlies these fascinating, alarming yet always beautiful works.

Press release extract 1994

MICHAEL CLARK – FIVE WOUNDS

David Coke

Art of England February 2008

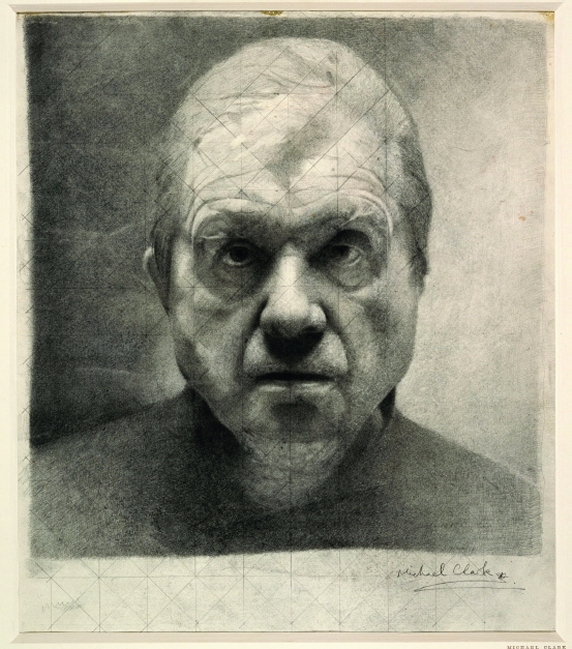

Of the many and varied works on paper in an exhibition at the British Museum in 1993,it is the image of a minutely drafted human face that sticks in my mind. Seen directly from the front, the subject glares out at the viewer with a disturbing intensity. Initially, it was the technical skill,the controlled chiaroscuro and the fine finish that entranced me, but as soon as I looked at it more closely, I knew I was looking at more than just graphite marks on paper, and that there was a very real and melancholy spirit caught within the artist's visual vocabulary - the sitter's presence accentuated by his absence. In this apparently photographic and simple drawing,the material and the spiritual had truly been united - the Holy Grail of all true artists. Looking finally at the label, I saw that the subject was, of course, the great modernist painter Francis Bacon, and that the artist was Michael Clark, a name that was new to me at the time.

Clark had become a friend of Francis Bacon after gate-crashing the notorious Colony Room club on Dean Street in Soho; through Bacon he met the indomitable Valerie Beston of the Marlborough Gallery. It was Miss Beston, Clark's first patron, who cannily suggested that he should make a portrait of Bacon, knowing that he had the ability to truly capture the complex and tormented soul of the older man.This led to a series of works, drawn and painted, six of which were later purchased by Miss Beston, along with several studies of Muriel Belcher and of Ian Board, proprietors of the Colony Room. The Bacon series, dating from the late 1970s to the early '80s, which comprise the first major works of Clark's mature artistic style, admirably encapsulate the feelings of loss, of entrapment, and of the outcome of violent confrontation that so often mark his work.

Bacon's influence, particularly his fascination with the fragility of human life, and the two artists' deep understanding of each other, run like an artery through the body of Clark's work. Clark considers Bacon's studio, where few people ever gained access in his lifetime, to be almost a hallowed place, a room where some of the greatest works of the 20th century had been produced.

Despite developing similar abilities, and being highly thought of for his haunting face-works, Clark does not consider himself to be a portraitist, any more than Bacon did; he believes that artists have a more important job, that of transforming base materials into higher realities, and of raising important questions in the minds of his audience, often unanswerable questions about the nature of life and ideas.To achieve this, he makes a purposeful decision to represent likeness by unexpected means, and to find a new language to express the presence of abstractions. His conclusions often lead to extremes of understatement.

Indeed, very few of the thousands of visitors to Chichester's great medieval cathedral realise that it has been transformed into a remarkable conceptual work of art by this same artist.Through the introduction into the building of five tiny, jewel-like paintings of flesh wounds, placed so as to replicate the wounds of Christ crucified - two at the west end for the wounds in the feet, one in each transept for the wounds in the hands and one in the sanctuary for the wound in the side - the body of the cathedral has been transmuted by Clark into the body of Christ. Fewer still will recognise the direct ancestry of Francis Bacon in this enigmatic work, and through him, to his one-time teacher and lover Roy de Maistre, famous for his 'Stations of the Cross' in Westminster Cathedral.

Having seen the drawing at the British Museum exhibition, I knew that Clark was an artist I wanted to work with if the chance were ever to arise. It did just that a year or so later when the Trustees of Pallant House,the Chichester gallery that had been opened just nine years earlier, charged me to find an artist who could not just capture a likeness of the retiring chairman, Philip Stroud (who had known de Maistre), but also produce a work of art worthy of the existing collections at the gallery.

As soon as Clark knew of the close connections between Pallant House and the nearby Cathedral (Pallant House had been originally opened to show the modern art collection of the retired Dean of Chichester, Walter Hussey, who had been an early patron of Henry Moore, Graham Sutherland and John Piper) he tempered his reluctance to undertake a portrait commission, and advocated the possibility of building on the relationship with the cathedral by offering to install there a new work that would refer back to the portrait, but that would be more in tune with the trajectory of his conceptual concerns.

This new work, the 'Five Wounds' (1994), loosely inspired by the grisaille 'Dead Christ' of Andrea Mantegna, is at once an exquisite set of miniatures representing human mortality, and an immense celebration of faith. It highlights other contrasts as well; its newness contrasting with the age and history of the building; its reserve with the size and visual power of the other modern artworks in the same church; its easy accessibility with the distance of other artworks; its human frailty with the massive structure within which it is set; and its warm colour with the cold grey setting.

So, if they are so alien, why do they sit so well in their context? First, because they were created specifically for that site, and their subject is eminently appropriate to the setting, working with it to create something larger than both. But also because of their geometry; the size of each panel is 2.236 inches square, that number being the square root of five - the five wounds, the five senses, or the five points of the pentagon formed by the paintings in their space.This number also relates to the Golden Section which would have been incorporated deep into the geometry of the cathedral itself by the medieval builders.

In the last edition of this magazine, Charles Darwent explored 'Drawing Breath', another conceptual work by Clark, a sound sculpture where the visual element has been altogether foregone. Like 'Drawing Breath', a site- specific work on the threshold of Janus, a Soho sex shop, the Chichester 'Five Wounds', is loaded with deeper layers of meaning and symbolic significance. Both works refer to Arthur Rimbaud, the French Symbolist poet, and to his exploration of the esoteric relationships between many elements of our life, specifically his belief in the synaesthetic path between vowels and colours, and in the alchemical ability to transform base materials into higher spiritual ones.

The 'Five Wounds' belongs to a very ancient tradition of devotional images, in which Christ's wounds are seen as a portal, an opening to something deeper. The collections at the British Museum, which include Clark's drawing of Bacon as well as a 'wound' on paper, also include a medieval ring inscribed with an image of Christ with the instruments of the Passion. The five wounds depicted here are each described as votive wells: the wounds in the feet 'the well of pitty' and 'the well of merci', those in the hands 'the well of grace' and 'the well of comfort', and that in the side, seen as the most powerful,'the well of everlasting lyffe.'These same titles are given to each of the Five Wounds in Chichester, inscribed on the reverse, and each title, colour-coded and given its relevant vowel according to Rimbaud's rule, is accompanied by a mineral fragment - an occult and unexpected metaphysical element of these works; in the case of the side wound in the Sanctuary, the mineral is a piece of iron meteorite, the other-worldly metal used by the ancient Egyptians to fashion ceremonial scalpels. This most significant of the five wounds, which symbolises rebirth or everlasting life, is transformed in the work of metaphysical poets like Richard Crashaw, into an eye or a mouth; Crashaw believed that his verse made the body of Jesus visible through its concentration on his wounds, giving his own poetry the ability to heal others. The links between wound and mouth have always been strong, particularly in medicine, where the edges of a wound are referred to as the 'lips'.

As the culmination of a series of paintings around related subjects, the 'Five Wounds' pulls together many of Clark's ideas and obsessions, which are based on his fascination with the susceptibility of our skin to damage, both from our own abuse of it and from external forces, and with the paradoxical beauty of wounded flesh. Clark provokes our emotional and intellectual reactions to different types of wound - whether self-inflicted or for ornamentation, from surgical intervention or brutality, from sexual arousal or disease. His faces, too, scrutinise human vulnerability, his subject often appearing to be his victim, trapped on the canvas or paper, his soul laid bare for all to see like a butterfly pinned to a board.

By the early 1990s, Clark's investigation of humanity had taken a more abstracted turn, questioning the ways we create a likeness of an individual without merely copying their face, clothes, body, posture. Alchemy and fetishistic associations inform these disturbing works, which stretch the limitations of artistic media as well as our understanding of the way we look at other people. Besides Bacon, Clark's other victims include Lisa Stansfield ('Vanitas', 1992), Derek Jarman ('Seer', 1993) and Nic Roeg ('al-jebr', 1999) (the two latter in the collections of the National Portrait Gallery), all portrayed in unexpected ways and all received with both acclaim and outrage - necessary prerequisites for any worthwhile artistic endeavour. More recently, Clark has moved further away still from traditional artistic media, as he questions, through photography, film, sound and performance, how we relate to our corporeal self when faced by the new uncertainties produced by HIV and MRSA, by disturbing medical and technological advances, by the decoding of the human genome and the forensic use of DNA, and by home-grown suicide bombers. In all these cases, our lives and identities can be threatened by phenomena that should be harmless, or even healing.

'10:07-09',a digital projection commissioned in 2002 by Winchester Cathedral for Holy Week develops the idea in Clark's work that the wound is a way through, a way to a deeper truth.The dominant image here is that of a key turning in a wound, projected onto the left hand lock of the cathedral's west door, while tied to the key with blue surgical thread is a nail. A verse by Richard Crashaw,'And the nails as keys unlock you on all sides,' is projected onto the opposing lock. As with the 'Five Wounds' in Chichester,'10:07-09'isloosely inspired by the 'Dead Christ' of Andrea Mantegna, turning it, like Crashaw's verse, into a metaphor for the crucifixion and resurrection of Christ, a truly devotional work that forces us to re-think our beliefs, and that provides new structures upon which to build them.

Michael Clark has never avoided difficult or epic themes; on the contrary, he has always embraced them as a valuable driving force in his art, and has treated them with a rigorous sensitivity. Through his work, extreme revulsion and enormous beauty come together in harmony. His work initially enthrals the viewer by the sheer beauty of its execution; then his microscopic investigation of pain and beauty appeals to our most basic and primitive senses. The mesmeric effect of the work draws us in and, vortex-like, involves us even before we know what we are looking at. Because of these qualities in his work, there is a growing recognition that this remarkable artist is one of a very few who is creating truly new and original works of art both ecclesiastical and secular, works that challenge and extend accepted iconographies, but that spring from his own beliefs and doubts, as well as from long, careful and intelligent thought. He is not trying to impose incomprehensible abstractions or vacuous concepts on an unwilling audience; nor is he interested in the shock tactics of some of his contemporaries, despite his preoccupation with popular taboos. He is, rather, offering his own very personal interpretation of philosophical and doctrinal tenets to anybody responsive and open enough to embrace it.

© 2007 David Coke, 3 December 2007.

|