|

The Gardener - Michael Clark's portait of Derek Jarman by The Gardener - Michael Clark's portait of Derek Jarman by Anita Phillips

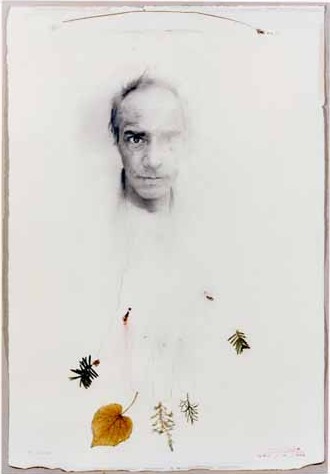

Michael Clark drew the film-maker towards the end of his life, when he was a man facing sickness and death. The drawing has a distinct and immediate impact, foregrounding as it does the quality of personal courage of the sitter. You are powerfully drawn to the face, you have a sense that the sitter trusted the artist to see into the eyes, to do much more than observe. With the image of the hand below there is the evocation of stigmata, of the passion of Christ, beaten, tortured, before being nailed to the cross. There are echoes of the Sacred Heart images of Christ, in which he holds out one hand, showing the marks of the crucifying nails, and with the other indicates his heart which is exposed through an open wound, red, glowing, full of love. Christ, the perfect man, tried to short-circuit violence and inhumanity, to stop the killings, by giving us his body as the sacrifice that would last throughout eternity. But one frail body is not enough to swallow hell.

Half of Jarmanís face is commandingly, intensively alive. The face is one that is used to being looked at, being adored, and of turning that around, becoming the viewer too, dynamising sexualising the mutual gaze. He was someone with whom to become infatuated, not just because he was good-looking but because nothing was kept back, it was all there for you if you wanted it. He knew you would want it, I mean want to just look at him, take him in. The opening of the heart that Clark evokes through the outline of the open hand signifies a kind of hospitality that the man offered to anyone who wanted it. I wanted it myself. My own visit to his flat in Soho must have happened at about the same time as this portrait: Jarman was by this time nearly blind and didnít immediately recognise me, having invited me a week earlier. The flat was bleakly empty, his possessions already given away to friends and art colleges, divesting himself of material possessions in advance of his death.

The other half of the face is the death mask. Clark has represented a man whose death is happening to him, encroaching upon the very face of him, via an intense light that is bleaching out contour and feature, washing out expression. So that what we see is the symbol, something like an ancient engraving upon a medal or urn of a great prince of ancient Greece, both beautiful and heroic, but banalised in memorial. Clark has drawn a man who has already become mythologized, deified and reified, a man who was already, partly, the sum of other peopleís memories and projections. In this portrait, Derek Jarman faces a double death, that which is attacking his physical body and that which attacks his living complexity through the simplifications of mythology. But Jarman is also shown as he really was, still living.

© 2000 Anita Phillips

Catalogue entry from 'Behind the Mask' by Lucy Whetstone

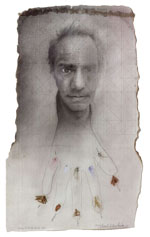

In the twentieth century the distinction between public and private has become less clear. Michael Clark's two portraits of the artist, film maker and writer Derek Jarman were painted just before his death from AIDS. Rather than a commission, the works were a result of the artist's personal interest in Jarman and his work. In both paintings, layers of references to Jarman's professional interests are subtly interwoven with a compelling image of the man himself. Study for the Gardener, through its title and the addition of botanical specimens, allude to Jarman's passion for gardening which formed part of his professional and personal life in his garden designs, in the film The Garden and in the evolution of the garden at his home in Dungeness, Kent. More intensely personal are the blurring of the left eye and the patch of colour beneath it (blood), references to Jarman's intermittent blindness and the bleeding that occurred on his face as Clark was working on the portrait.

The painting is however, as much a testament to the artist's own views on mans mortality as Jarman's own. The hand which grows downwards from Jarman's head, suggests the passage of life, following the belief that associates the thumb with the metal silver and life, and the little finger with lead and death. The inclusion of a quotation from Jean Cocteau, "we look at death at work every day in the mirror", was a favourite of Francis Bacon, whom the artist also knew well and painted, and it further emphasises that this is a portrait not just of Jarman, but also of the people and philosophies that have inspired the artist himself.

© Lucy Whetstone (Curator) Catalogue entry Behind the Mask - The Hatton Gallery University of Newcastle upon Tyne - March - May 2002. - The Bowes Museum June - August 2002 |