|

kamera.co.uk film review © Sameer Padania

Perhaps the most succinctly insightful critical response to the work of Nicolas Roeg might be Michael Clark’s portrait of the British director in the National Portrait Gallery in London. Entitled “al-jebr”, this Arabic word means “the bringing together of broken parts”. There are certain keywords that recur in critical appraisals of Roeg’s work: fractured, shattered, collapsed, labyrinthine. This is no less true of his now thankfully re-released 1973 masterpiece, Don’t look now, which forms part of an early body of work, including 1970’s astonishing Performance (co-directed with Donald Cammell), the deeply pessimistic Walkabout (also 1970), and the glacially prescient The Man who Fell to Earth (1976).

Al-Jebr (Michael Clark's Portrait of Nicolas Roeg) by John Walsh

Suspended inside glass, the face of Nicolas Roeg, the British film director, hangs inside a gourd like a stern news-reader inside a nasty television set. It is impossible to consider the “face” of this portrait without being aware of the three-dimensional nightmare that lurks behind it - the twisted voodoo plait that dangles beneath, the hints of flesh that gradually come into view, the damaged, messy carnage of hair, skin and adornments that are finally revealed. Michael Clark’s extraordinary new work offers something never seen before: the world that lies behind the face of a portrait. The concealed imagination. Nicolas Roeg peers out from the almond-shaped mandorla frame with a querulous dignity. He looks at us like a suspicious warder who has come to the porthole of a cell door to inspect the life-form within. He doesn’t like what he sees, but he must look, with the stern gaze of a moral inquisitor. He regards the world through glass just as he has regarded it, all his career, through a camera lens, both recording and creating strange and obsessive worlds of violence and doomed striving.

His face is thrust forward so that his shoulders seem puny and far away – like Alice, in Wonderland, when her serpent neck had borne her head away from her body. In Roeg’s magnified head, the eyes command the picture. They insist on your attention, for they tell two stories. His right eye is bright with a visionary gleam, an eager translucence that seems to emit light as well as reflect it; the left eye, by contrast, is dulled, occluded and full of woe – a disappointed eye that seems to droop under its disfiguring eyebrow, as Roeg’s father’s face was disfigured by war, as characters in his films suddenly reveal ghastly facial blemishes or transfigurations (the dwarf murderer in Don’t Look Now, features-less alien in The Man Who Fell to Earth). Furrows of melancholy cut a deep T-shape in Roeg’s brow, like a crucifix without a head: and a multiplicity of Gethsemane emotions – suffering, resignation, detachment – contribute to the picture’s mood. Signs of ageing, in the pouched cheeks and wispy hair, are countered by the immediacy - the stroppy thereness – of the director’s gaze, the unsmiling set of the mouth. Though not an old face, it’s a decadent one. It has seen more than is good for a human.

Suddenly you take in the asteroid shower of tiny blemishes that pock the portrait’s surface – sand? pebbles? dust boulders? – and see the whole work not just as a likeness or an image but a construct, like a work of tribal craft abandoned in a Borneo bunkhouse and discovered, with a thrill of horror, by travellers from a more sophisticated world…..

The frame for Roeg’s face is like no other. It’s at once a gourd, a void, a plenum, a womb and a brain, pricked and festooned with symbolic artefacts, all of them expressive of the director’s troubling imagination. It’s an extraordinary encapsulation of the feral underworld that Roeg locates beneath all our civilised endeavours , our greed and pretensions, our hope of finding sense or love or reassurance in a world of barely –suppressed violence and fear.

Several remarkable ”mixed media” went into the construction of the Roeg portrait - syringe needles, lead weights, beeswax, a bee, oil, acrylic, linen, glass… The five hypodermic needles are coded in the colours (blue, green, red, white black) that, according to Rimbaud, correspond to the five vowels. Five lead fishing weights hang from them, silvered and gilded to form a dangling fetish object that draws together the Belgian Congo (where Conrad set Heart of Darkness) and the world of self-destructive need that characterised Performance, Bad Timing, Walkout, Eureka, Track 29…

The dead bee perching on the gourd’s upper slopes is a nod to Napoleon, with whom Roeg shares a birthday (August 15) and who used to carry a bee-shaped amulet as a talisman. The matted mess of hair and traumatised flesh, which causes the viewer both to flinch from the exhibit and inspect it with horrified fascination, is a nod to two deaths in Roeg-world: the prospector who blows his brains out in Eureka, and the bullet that burrows through the rock star Turner’s brain at the end of Performance.

The monstrous flesh drum which implicitly encases the director’s imagination is a calculated assault on our notions about the purity of art. Like Rachel Whiteread’s inside-out house, it shows a mind turned outwards like a grapefruit skin, exposing its gross inner pith, its intestinal workings. It suggests that trauma, decay, revulsion, strange gods, odd superstitions and wayward playfulness are as likely to govern the artist’s vision as are clarity, harmony, structure.

It’s a horrible casing – both brain and belly, the first home of the slowly-gestating work of art, and its informing intelligence – inside which anything or nothing may reside. In fact, it contains two secrets. In mid-composition, the artist asked his subject for a secret, to be written on a slip of paper; Roeg complied and Clark wrote down a secret of his own. Both slips of paper are now inside the work, tantalisingly, un-get-at-ably secret, until the piece is opened up and it’s magic dispersed.

Michael Clark is a leading portrait painter, who has, for years, pushed the boundaries of portraiture as far as they will go. His combination of hyper-precision and bleached of portraiture as they will go. His combination of hyper-precision and bleached melancholy has been seen in portraits of Francis Bacon, Muriel Belcher of Soho’s Colony Room, and the late Derek Jarman (Clark’s portrait of the last-named hangs in the NPG). Five years ago he branched out into anti-portraiture, wearied by the requirement that portraits must be likenesses of their subject.

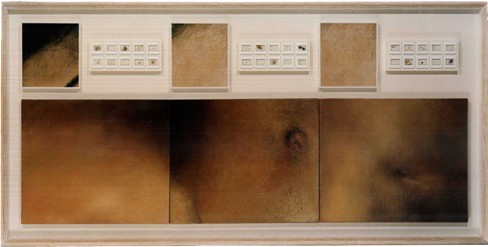

Some may lose their faith Some may lose their faith - Collection The Artist © Michael Clark

His bold triptych, Some May Lose Their Faith, offered three landscapes of flesh with exploded wounds, livid in pink, orange and bruised blue. Since we can truly identify Christ’s dead body only through the wounds made by nails and spear, Clark argued, do not the wounds alone constitute a portrait? Later he blended the two dimensional portrait with the installation piece in Vanitas – a double-canvas that showed, on the front, the saintly face of Lisa Stansfield the singer and, on the back, a terrible flesh wound buried deep inside her; while a 24 –frame, one-second video clip took us through the strange journey by which it got there.

1/4 second film fragment 6 colour photographs 1/4 second film fragment 6 colour photographs - Collection V+A © Michael Clark

Clark’s new work leads us into unsettling territory. To provide a portrait with an accompanying brain is one thing; to make it so boldly grotesque yet so tightly symbolic, so repellent yet so trophy-like (the prize exhibit in the headshrinkers’s corner of the longhouse), and to insist that the portrait of an artist should embrace all dimensions, including the imagination, and all available media, including hair, blood and dead bees – that is something quite else.

Nothing like this has been seen at the National Portrait Gallery before. It could change the form of British portraiture for ever.

© 1999 John Walsh |